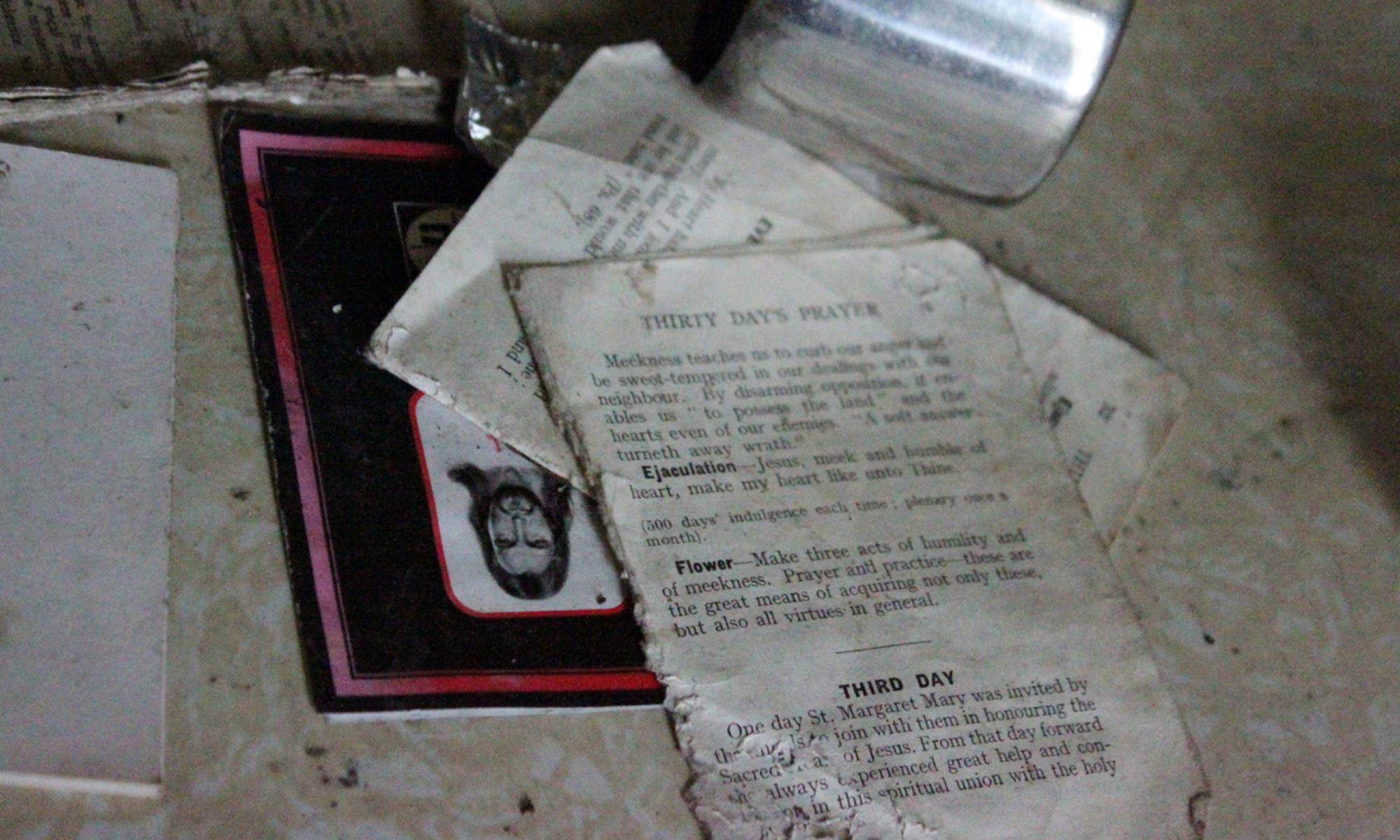

In Ghost House (2007-2011), I documented several abandoned houses in Ireland. From left-over personal belongings, including such intimate objects as letters, and religious artefacts, I reconstructed the lives of their former occupants. Some of them had died, leaving no heir, but others had emigrated to America to join family members already settled there, because of the poor economic conditions in rural Ireland. They were economic migrants: from what I read on their letters, they took their Irish catholic values with them as they left. Their only motivation to leave their homeland was economic.

In 2009, as I visited my grandmother in France, I was struck by the similarities between her house and the Ghost Houses: the same catholic knick-knack, the same décor frozen in time. But I had not been driven to leave my home town solely by economical reasons: for as long as I could remember, I had longed to escape its oppressive atmosphere and narrow-minded values. Like countless other bright lower class kids born in the middle of nowhere, I was an intimate migrant, forced out of my home town not by lack of work, but because of a fundamental discrepancy in out belief system.

In 2011, I temporarily moved back to my own personal hell-hole, and at the same moment my grandmother died. I documented her house one last time before we started to slowly empty it. For a year, the house remained unsold, almost turning into a Ghost House itself. As I contemplated one last time my grandmother’s crucifixes and Virgin Mary, I wondered why I had been so driven to document similar places in Ireland, as well as Magdalene Laundries, a place where girls very much like me ended up locked when they were not so lucky to escape. Can you ever escape the social strata you were born into, or are your thought processes forever determined by it, be it in the form of acceptance or rejection? Is Catholicism like addiction: you can take the decision not to act on the impulse, but you cannot reverse the subtle way it warped your thinking patterns?