My first foray in art criticism! Review of Manifesta Biennial in Palermo for A-N from the subjective perspective of an artist working with queer and feminist themes and an underground ethos.

My review has been featured in GLIMP, free international queer art newsletter from the Netherlands, September 2018 edition.

Manifesta 12: Chercher La Femme, Chercher Le Queer

I applied to for a bursary to visit Manifesta 12 partly out of interests for its core themes of migration, and space/place as politically charged, especially as sites of repression, which I explored in my own work (Ghost House, Disciplinary Institutions), and partly out of interest for visiting Palermo itself, where Luchino Visconti, an artist I greatly admire, had made his masterpiece The Leopard.

At the time of applying, I was unaware of the 2014 controversy of Manifesta 10 taking place in St Petersburg with direct funding from Putin’s government, despite several calls from various artists and organisations to either withdraw and boycott or organise with more curatorial and financial independence, in protest of the Russian government’s repression of LGBTQ rights, and human rights in general. As an artist dealing with feminist and queer themes, this new information influenced my perception of the Biennale.

My review will first explain my reservations and criticism towards the Biennale’s general curatorial concept, which I perceived to be heavily biased towards a specific type of artwork rather than presenting balanced, varied approaches to the mandated subjects, then focus on the few artworks that I perceived dared to go beyond the restricted view of the curator and engaged with the subjects in deeper, more thoughtful, critical and independent ways, and therefore stood out for me.

Manifesta 12 is split into three curatorial themes, each investigated both generally and within the context of Palermo, with themes occasionally overlapping. The Garden of Flows explores plant life, gardening and climate change. Out of Control Room examines geopolitical power and migration. The City on Stage, the theme explored most closely in relation to Palermo, focus on the urban life of the city.

Amongst the 3 themes, I was most interested in Out of Control Room as I regularly explore repression of minorities and social control in my own work. As it turned out, it was the theme for which I was most disappointed with the curatorial process. I felt a disproportionate quantity of artworks, most of which especially commissioned for Manifesta, explored the theme purely from the angle of collating and visually presenting big data about various forms of violence taking place in contexts of armed conflict or migration, without ever digging into the controversial questions of ‘Who benefits from the crime?’, ‘Who is pulling the strings?’. In short, too much of the work focused on the factual ‘What’ and ‘When’, but shied away from the ‘Why’, and even to a certain extent from the simpler issues of ‘Who’ and ‘To Whom’.

‘Signal Flow’, a video installation by Laura Poitras, documents the US military presence in Sicily. ‘Liquid Violence’, an installation by Forensic Oceanography looks at the militarized border zone of the Mediterranean, leading to the death of many migrants at sea. Both works are mostly detailed records of strikes or deaths, and their factual circumstances. ‘Unending Lightning’ a video installation by Cristina Lucas documents the history of aerial bombardments and bombings over civilian targets, from the first, in 1911, to the present day. World wars and civil wars, terror campaigns and random bombings are all gathered in a database assembled by several research groups over the last five years, that methodically counts who killed whom, how many civilian casualties there were, when and where. But because the work lists together so many events that happened in widely different geopolitical contexts, motivated by wildly different causes or ideologies, whose only common denominator is the ‘What’ (civilian death by airstrike), if feels even more devoid of critical context and analysis than the previous examples, which at least narrowly focused on one specific, coherent type of event.

While I fully relate with the artists’ drive to expose human rights abuse, when bombarded with such accumulation of data, my mind starts wandering in wild directions, about Western regimes silently supporting dictatorships in the Middle East for decades, the extent of human rights abuse taking place in far away countries that never end up landing on the shores of Fortress Europe, the shadowy links between repressive regimes abroad and authoritarian, regressive groups in Europe, and the refusal of the work to engage back with me about the complex underlying causes of the carnage it catalogues leaves me frustrated.

When looking at most of the work, I kept wondering whether I was looking at designed/animated infographics made for a newspaper, a mainstream news documentary aiming to present a ‘neutral perspective’ (as opposed to artist’s documentaries where the subject is filtered though the artist’s critical and creative perspective), or a video clip for a charitable fundraiser that sticks on purpose to dramatic human stories without digging into the more controversial political or economic underlying causes. All these media have their use, but Manifesta 12 is world class art event, and I would have expected it to tackle its chosen political themes from more controversial and critical angles.

I asked myself what may have been the drive behind this curatorial focus on big-data and fact-gathering. At first, I thought it might have been a deliberate intellectual response to ‘fake news’ and the rejection of facts and experts during the Brexit and Trump campaigns, but these events happened in the second half of 2016, by which time the curating and commissioning process must have been advanced, so this theory most likely does not hold. I then looked into the origins of Manifesta: Manifesta was created in 1994, aiming to ‘enhance artistic and cultural [international] exchanges after the end of Cold War’. Extrapolating and venturing into my own highly subjective perception (please consider this sentence a disclaimer), I felt that the creation of Manifesta in a context of East vs.West conflicting ideologies may shed light on the curatorial angle, except in the context of the migration crisis, the concept has shifted to North vs. South oppositions. While a whole third of the program was devoted to power, repression and migration, the vast majority of the works explored power dynamics from country to country, with affected human beings identified solely by their nationality/geographical origins, and a country’s population was mostly presented as a homogeneous cultural entity. Other forms of repression, gender-based, against minorities in a given country, or between conflicting ideologies and values within a country’s population, the very conflict that drives cultural change, were mostly ignored. Consequently, the works that stood out for me were the ones that offered alternative or counter- narratives.

‘Purple Muslin’, by Erkan Özgen. Photo: Melanie Menard.

Purple Muslin, a documentary video by Erkan Özgen created in collaboration with women refugees in Europe and Turkey who fled the war zones of northern Iraq, records in interviews the women’s experiences of violence, repression, and being forced to leave their country to survive. The video made for harrowing viewing and while it focused on recording testimonies without providing context (ISIS is named as the perpetrator but the video does not dwell on who funds/supports them), the work shed light on uncomfortable questions that none of the other migration-related works addressed: that women bear the brunt of repression and violence, both in repressive regimes and in war zones. And also, since a lot of the women interviewed lived in refugee camps near the Irak border, do we (Europeans) only care about human rights abuse when its victims land on our borders, while washing our hands off repressive regimes far away?

‘Pteridophilia’, by Zheng Bo. Photo: Melanie Menard.

Another human group bearing the brunt of repression and violence, namely LGBTQ+ people, often sent back to unsafe countries when their asylum requests are rejected by European countries, was conspicuous by its absence. The only explicitly queer work in the whole of Manifesta’s program (compare with last year’s Venice Biennale program…) is Pteridophilia, a video by Zheng Bo exploring the ‘eco-queer potential’ of sensually connecting with nature and ‘relying on bodies rather than language to initiate affective relations’. The work is playful and sexy, and appealed to my love of camp and eccentricity. But it felt like a slap in the face that the curators’ token queer work did not address LGBTQ+ repression amongst a program so heavy on power and migration, especially in light of the previous St Petersburg controversy. Like our queer lives do not matter.

Indeed, to find work addressing LGBTQ+ repression, and artist-activists fighting back against the laws of their own countries, one had to dig all the way into the collateral program (of independently curated fringe events): the Visual Arts strand of Sicilia Queer filmfest curated a group show of contemporary artists from Beirut, exposing the situation of LGBT rights in Lebanon, and offering glimpses of the clandestine queer scene of the city, including a lot of compelling photographic work, from the stark documentary to the aesthetic and conceptual. But the show was only on between 30 May and 30 June.

‘Night Soil’, by Melanie Bonajo. Photo: Melanie Menard.

‘Night Soil’, an experimental documentary by Dutch artist Melanie Bonajo, alternating social documentary and experimental hallucinatory visions, explores the disconnection most Western people feel from nature, and the consequent feelings of fragmentation, emptiness and alienation. The artist documents how her subjects, mainly women, because she believes their voices are insufficiently heard even today, tackle the problem by exploring alternative way of life outside the mainstream system, based on a different relationship with nature and a reassessment of ideas surrounding gender. Melanie Bonajo’s long term, intensive collaboration with her subjects, and the artist occasionally stepping into the frame herself, both observer and participant of a community, reminded me of Nan Goldin. ‘Night Soil’ highlights and celebrates the possibility for unknown individuals to affect change, both social and intimate, using their creativity and self-directed willingness to resist enforced norms, to make and be the change they want to see in the world. The work stood out for me as I felt it was the sole representative in the whole of Manifesta’s program of the avant-garde strand of contemporary art that, throughout the 20th and 21st century, defined art not as a remote/detached commentary on life, but as a laboratory for new ways of living, often operating at the intersection of the official art world and underground, alternative communities.

“I’m happy to own my implicit biases (malo mrkva, malo batina)” by Nora Turato. Photo: Manifesta.

Nora Turato’s “I’m happy to own my implicit biases (malo mrkva, malo batina)” is a spoken word performance (and a site specific recorded sound documentation of it when the artist is absent). The monologue is inspired by the Sicilian tradition of the so-called donas de fuera, that is “women from elsewhere”, who at the time of the Spanish Inquisition were treated as outcasts due to their unconventional powers and behaviour, and adapts it to a contemporary context by whispering secret stories, commonplace clichés and popular myths exposing contemporary sexist discourse and cultural normativity. The performance celebrates the concept of “elsewhere” (artist’s own description) or “The Other” (my interpretation) understood as a ‘space of emancipation within a contemporary culture that increasingly promotes the concept of inclusion as a deterrent to diversity and change’. I felt parts of the monologue satirising the worst cliches about the supposedly ‘irrational and hysterical female’, lines such as “I’m ready to cry, or combust or scream” or “I don’t need to make sense”, were especially powerful. The historical reference to the repression of female behaviour by the Inquisition, when read in parallel with Erkan Özgen’s documentary of female victims of ISIS in contemporary Irak, created a chilling historical echo across time and space, a powerful reminder never to forget past abuse and never to take progress and acquired rights for granted. As a piece of side trivia, the installation-performance takes place in the Oratorio di San Lorenzo, a stunning baroque oratory also home to the reproduction of a stolen Caravaggio. Fascinating women stories are collected in a series of related critical writing: ourladiesfromtheoutside.org

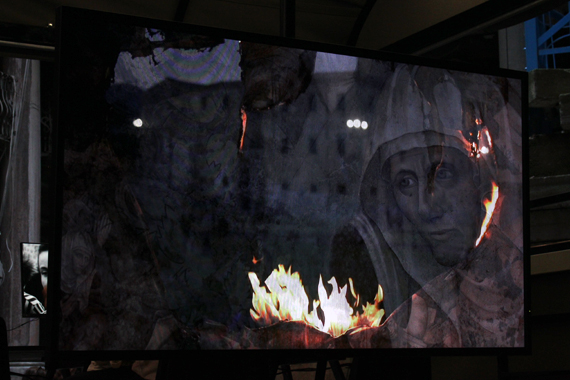

“Videomobile”, by MASBEDO. Photo: Melanie Menard

“Videomobile”, a video multi-channel installation by MASBEDO transforms an old van into a ‘video wagon’ that roams locations loosely associated to the cinema of the past, investigating Sicilian society and the history of Palermo through the angle of power dynamics, the genius loci, and the struggle for ideals. When roaming, the van acts a mobile video recording studio. When stationary (as I saw it), the van displays the collected videos on 3 small screens and 1 larger screen. The work stood out for me as it gave voice to ‘characters who had worked in cinema in an almost anonymous or marginal form, such as make up artists, extras or technicians’ alongside ‘better known figures such as directors, intellectuals, producers or politicians’, but gave each of them an equal voice. One of the clip pays homage to Pasolini’s Comizi d’Amore, where he interviewed women and children on the taboos of sex, love and freedom, and I could feel the influence of this ethos in the way the film-makers presented each of their subjects, whether famous or unknown, as a thinking, reflecting, autonomous individual, and gave them equal opportunity to address deep subjects if they wished. Some testimonies offered fascinating insight: collaborators on Visconti’s film described how his love for pomp and grand design infected their own later creative output. A musicologist explains how Visconti, when he adapted ‘The Leopard’, ‘turned a right-wing book into a left-wing story’, and how this process may have been related to Visconti’s own social ambivalence, coming from an aristocratic background but having leftist ideals. This insight made me reflect on how powerful and thought provoking political art can get (think of Visconti’s The Damned) when the artist does not shy away from exposing their inner contradictions, and playing with formal ambiguity, something I felt was sorely lacking from most of the overt but one-dimensional political work in Manifesta. In another very moving sequence, a photographer Letizia Battaglia speaks to a 10-year old girl Aurora ‘as though to her confidante’ and photographs her ‘as a mirror image of herself’. The artist shares her experience with the young girl in the most honest, profound, unpatronising manner: she talks of her younger self’s desire to take beautiful photographs, only to have it confronted by an uglier reality, of the profound meaning images can take when produced in a spirit of civic sense, quest for beauty and commitment to utopias and ethics. Live on camera, she relays onto the next generation how to think, create and initiate change in the world. In its unpretentious simplicity, I found this film extremely empowering when compared to other works which, while more overtly political, only extorted ordinary citizens to act after the artist had done the thinking for them (The Peng! Collective ‘Fluchthelfer.in. Become an Escape Agent’ and ‘Call a Spy’). Both Letizia Battaglia and a lesser known subject worked at the Palermo left-wing and anti-Mafia newspaper L’Ora and one of them (I can’t remember which and quote the film from memory) recalled how the newspaper acted as a local hub for artists and intellectuals of international caliber, including Visconti, the first point of call where they came to inform themselves of the local cultural and intellectual climate when they came to Palermo to work on a project. By paying homage to the ongoing work of local artists and intellectuals who, despite most of them remaining unknown, contribute to the ongoing cultural change and development of their city, long after the art stars have passed and moved on, the work could have provided inspiration for Manifesta to engage with local communities in a less patronising way, by thinking in collaboration with the locals instead of observing their lives but imposing external interpretations on them.