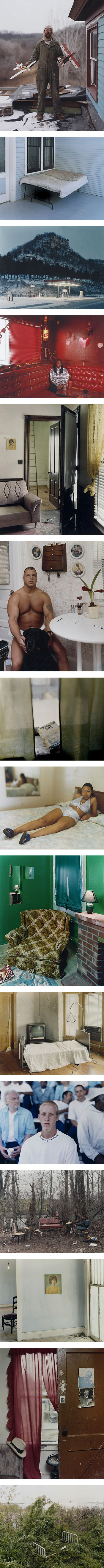

In a book surveying his career ‘Points between… up till now’, Robert Polidori discusses interesting issues in the introduction.

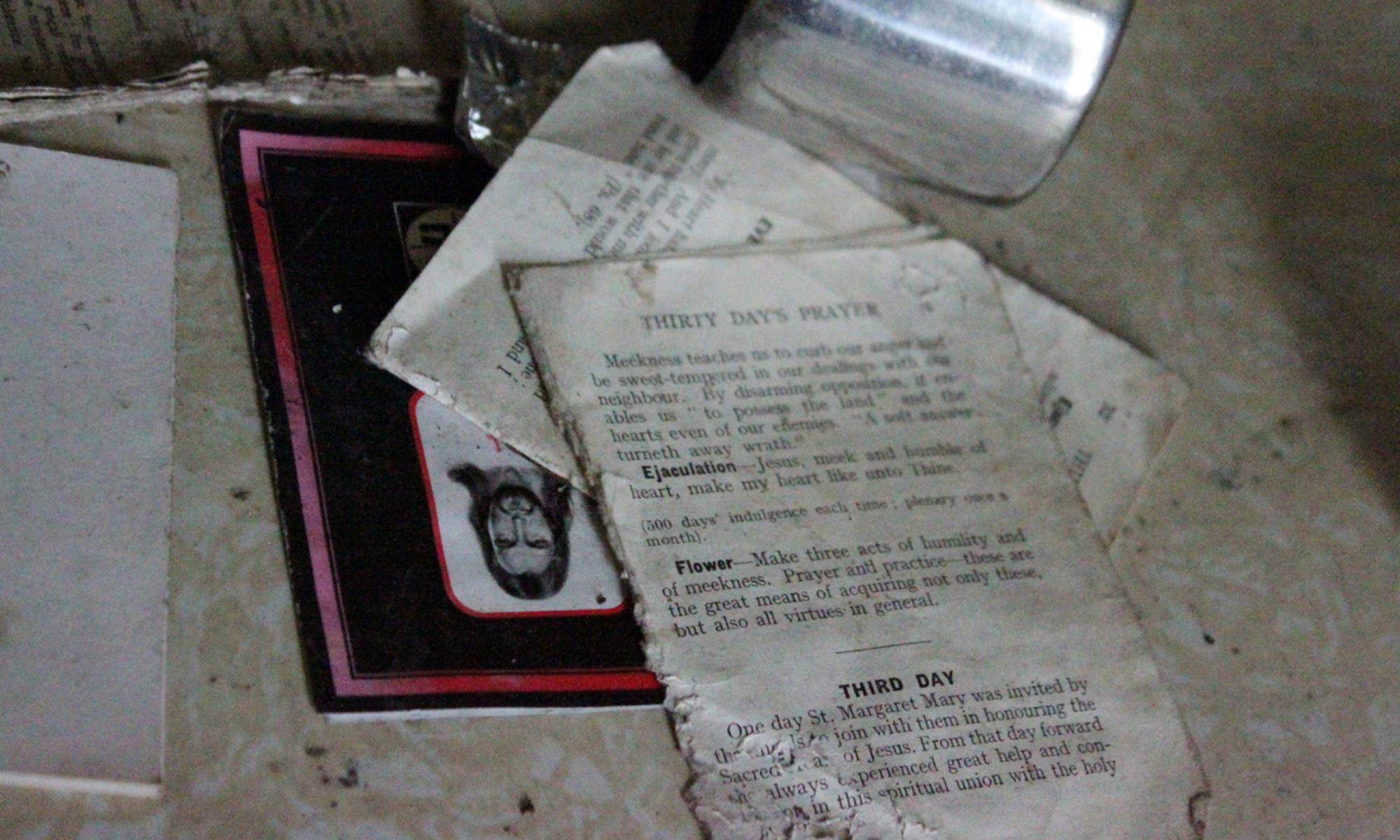

His interest in interiors started in 1987 when he photographed several New York flats whose owners had recently died and that had been looted. He says ‘On one hand, I came to consider the remaining objects as exteriorizing the personal identity and ideals of the dead individuals, yet on the other hand, these same objects, carefully accumulated over a lifetime, had now become a valueless heap of trace detritus for all the rest of us to wilfully discard (or vandalize). […] I perceived the rooms and their objects as some sort of sociological/psychological Rorschach test. I was convinced that there was something intrinsically historic and psychic about the subject matter that should be captured for posterity. Upon further reflection I came to regard the implications of the scene as being evocative of the human condition in general.’

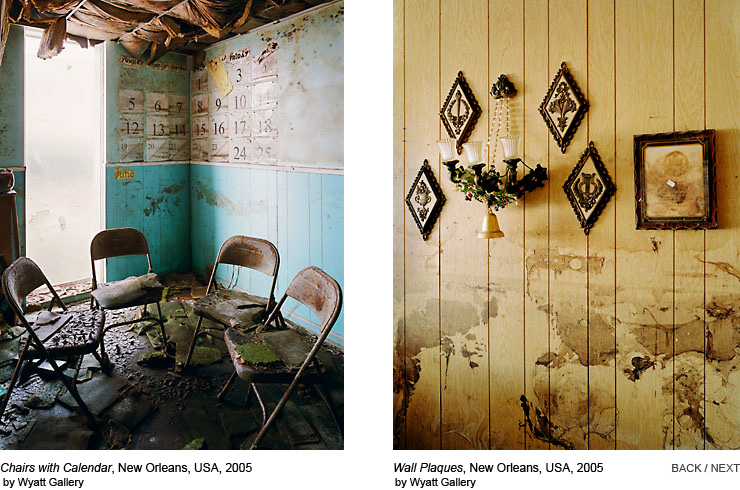

In 1994, he photographed buildings destroyed by the Lebanese Civil War. An old lady guided him through ruins and asked him ‘Do you feel able to take beautiful and pretty pictures of all this?’ He places this lady’s ‘dare’ (his own word) at the heart of the controversy surrounding his work. ‘My work has often been criticized as somehow lacking integrity because I transgress ethical principles by rendering tragic or violent situations as artificially “beautiful”. This “aestheticizing” is considered to be conceptually disturbing since, some argue, it brings a viewer to an experience by which realities and their causes are ultimately trivialised and misrepresented.’ On the particular reproach that his New Orleans pictures did not capture explicitly enough the government’s failure to properly maintain the levees, he says ‘a photographer cannot, after-the-fact, visually capture the long expired preceding moments, causal links or the far remote spatial tangent of a scene.’

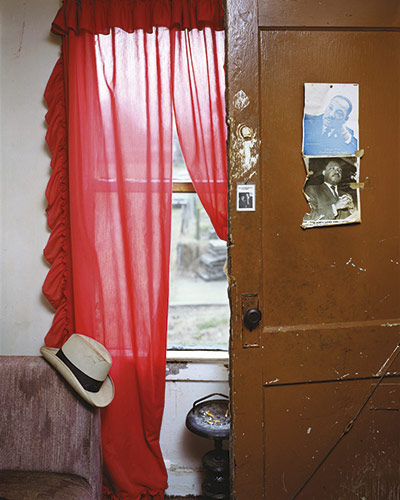

He states his favourite subject is ‘the psychological implications of the human habitat (the room)’ and links this to his ‘phenomenological interest in wanting to know what makes something or somebody tick’. He explains: ‘though most of my photographs are devoid of the human form, I have actively sought out rooms where the interiors were substantially and meaningfully filled with traces of human interventions. I consider these traces as being imbued with iconic references to what Carl Jung called the human psyche’s Super-Ego.How one wants to be perceived by oneself and others is infinitely more interesting to me than how one might happen to look.’

He explains that, while he had long ago abandoned the ‘intellectual notion of the existence of God’, the experience of photographing Chernobyl caused him to contemplate ‘the futility of Hope as a certainty’, and ‘the eventuality of foregoing the emotional crutch of brighter possibilities was infinitely more painful’.

About his feelings while photographing painful places, he explains ‘whenever the question comes up, I always answer that I feel nothing when I make these types of photographs. I feel before and after, but while executing them it is my belief there is only time to accurately act and react. I try to preload my emotions ahead of time but I don’t readily call upon them when I shoot. I want them to be instinctual yet non-conscious. Like surgeons in the operating room, the technical imperatives of photography demand complete mental acuity and a concentration that should not be disrupted by any background noise.’ I found this statement fascinating because it perfectly describes how I feel when I take my own photographs: you have to be completely focused on the act of seeing things, and you have to do the work not only well but quick because there is only a limited amount of time during which you can sustain the required depth of concentration.

![Walker Evans, untitled, [Genesee Valley Gorge] n.d](http://aok.lib.umbc.edu/img/evans01-s.jpg)