In June 2010, I attended a Symposium at Canterbury University: “Video art: between documentary and fiction”. Below are reading notes from this symposium. I was interested in it because it focused on lens-based images creating an awkward feeling of ambiguity regarding their documentary or staged nature, something I came to identify as a key concern in my practice.

Jon Dovey ‘The Limits of Vernacular Video’

Gaza Sderot: interactive video

The Himan Pet: Fake hostage video asking viewers to save the filmed subject

Derrida – Kate Modern on youtube ? the camera crew is no longer invisible

“Creative manipulation of reality” (author?)

Sarah Turner ’On documentary and Perestroika’

In Perestroïka, Sarah Turner repeats a journey to Siberia done 20 years ago (1987-88). Two friends present in the original trip are now dead at the moment of refilm in dec 2007- jan 2008

external events internalised

“Why and when does a documentary work display the truth of fiction ?”

memory, loss, photography, truth/fact, evidence

ourselves vs others and how it makes us

uncanny/real

refuses the duality between facts and the fiction of memory

psychogeography/dream

questions from audience:

Does the web esthetic of autobiographical filmmaking infect normal filmmaking?

I thought of Gus Van Sant’s Paranoid Park. Someone names Eli Harrison

“Who holds our story if the other is not here to do it?”

There is a more democratic access to cinema than to Art (just buy a ticket and be anonymous in the dark, compared to gallery environment)

Stiegler – Montage

Elizabeth Cowie ‘The Contingency of the encounter in documentary video art’

Rien que les heures – Cavalcanti – 1926 shows the city of paris and images of poverty

Badiou

Deleuze – intervals ????

Walter Benjamin “dialectical image” = image charged with history

Lauren Wright ‘The time between reality and fiction’

Curator at Turner Contemporary, Margate

picture by Turner of an imaginary landscape: he had read the description of it but never seen it

temporality shaped by artwork shaped by artwork and exhibition space

Bergson “creative evolution”

Matthew Buckingham: situation leading to a story

The visitors hears the sound but they have to walk around some walls to see the images (the sound continues in 2nd space with image)

the images are found footage: 4 rolls of 1920s home movies. The soundtrack is the artist’s comments/reflexions about what these films are about, who are the people in it, why the films have been thrown away, suppositions about unknown family drama and the possible cause of it.

Time as a collection of different temporal frames ? it does not let us collapse the different temporal frames

Robert Smithson, spiral jetty

Irit Rogoff ‘Bared Life – On the Documentary Turn in Visual Culture’

I missed most of this because I was watching the screenings.

Foucault: territorial ->population

Adam Chodzko ‘Latitudes’

ghost, echo, journey

Salam Cinema, 1995, Teheran

1998: Meunien ? he tried to find the 16 young victims from Pasolini’s Salo. Only one responded, he found doubles to replace the other original actors

The actor that responded was the one whose character did not do the final execution scene !!!

originally, Pasolini wanted footage from the cast party at the end of the film. But he finally decided against it, decided it was more disturbing not to explicitly tell the audience it was “only fiction”

-> makes me think of the ending of Greenaway’s The Baby of Mâcon

fabricated images from Milosevic trial ?check?

1967: David ?Holsman? Diary. Story of a director who obssessively records everything. Against the claims of “direct cinema”

Strawberry pickers

archive show “migrant workers” from East London come to pick hop in Kent in the 20’s and 30’s

the archives were edited by contemporary Romanian strawberry pickers. They said that the workers in the archive looked happier than themselves. By the end of the archive watching session, their attention start to drift and they start talking about themselves and their dreams

Chris Marker, Sans soleil: People sleeping in the tube, intercut with scary images of their dreams

An actor comes to an audition for a movie and pretends to be blind. When asked why by the director, he says he did it for the love of cinema.

A man burns himself with a cigarette, saying it is the only way to show the effect of Napalm (which causes a 3000°C burn compared to 400°C for a cigarette.

-> Does trauma/hurt guarantee authenticity ?

-> My own work on Magdalene/asylums ? Is it a cheap trick ?

Agnostic anxiety: not to know whether what you see or think is real or not, correct or not.

As a spectator, do you expect transformation from an artwork ?

Questions:

My question: in “A letter to Uncle Boonmee”, “soldiers occupied the place, killed villagers, forced them to flee to the jungle”. Yet the deserted houses are very clean (and houses in ireland show how very quickly they deteriorate). So this image hints at recent trauma/violence. This is reinforced by the presence of fictionnal soldiers played by local teens. Are they real houses or stage design ?

-> previous speaker: trauma/hurt guarantee of authenticity

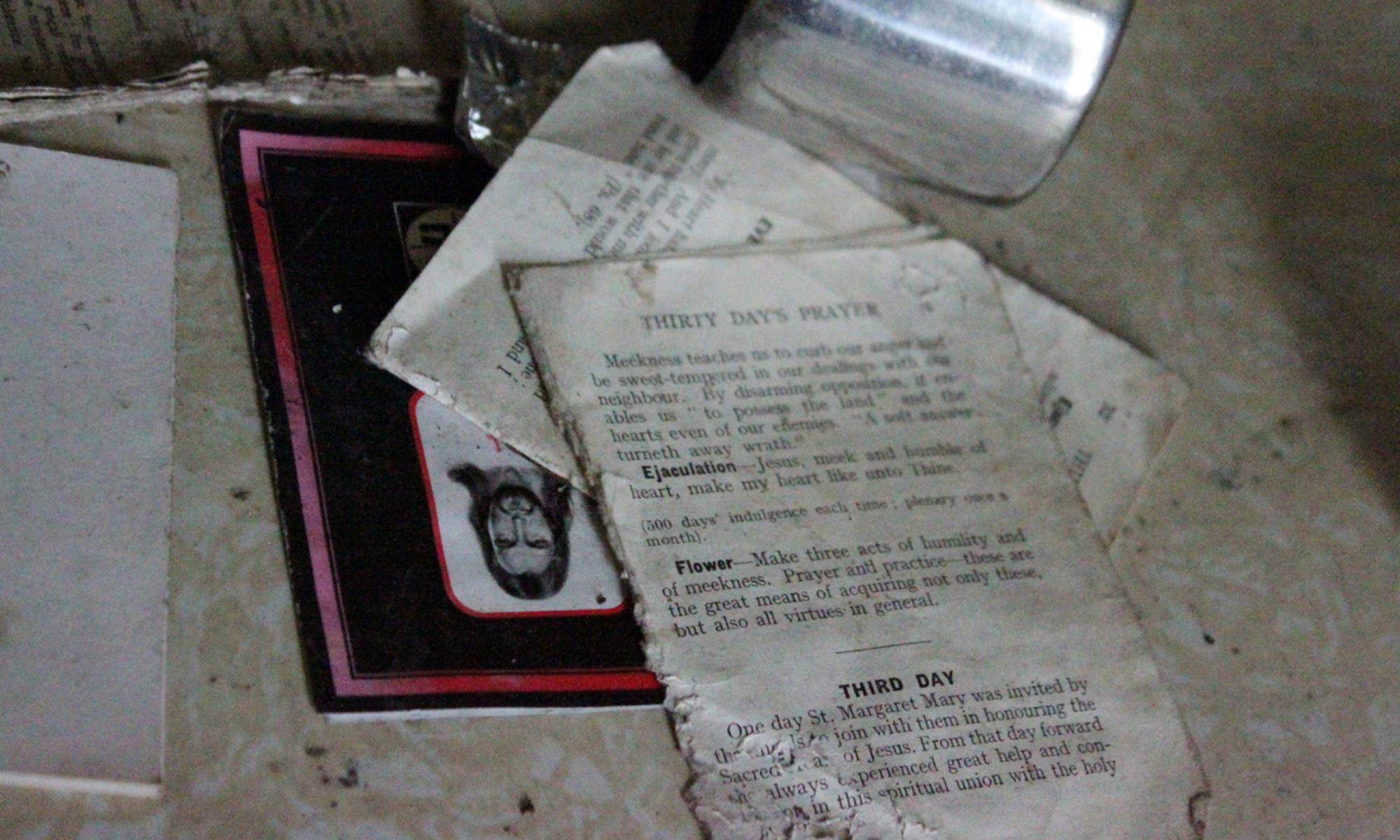

-> I point out to a urbex forum discussion of the moral implications for the artist/urbexer of picturing recent trauma. Are the moral implications different between taking pictures of Tchernobyl and post Katrina NOLA?

Michael Newall

Pyramid – Adam Chodzko: Folkestone residents reaction to the appearance and disappearance of an otherworldly object, the pyramid.

International God Look-alike competition – Adam Chodzko

Philosophy of Art

Cognitivism: the value of Art is to offer knowledge/deepen understanding

Bourriaud – relational aesthetics: art that facilitates communities

-> critic of it: it designs only social situations where there are no conflicted interests. Different from real life.

-> he argues that activist art can change social situations, as opposed to relational

-> my objection: Activist art gives an answer to the audience (thesis, propaganda) whereas relational art make audience make their own meaning

-> later I actually get the opportunity to ask this and here is the answer: he refered not to propaganda/thesis art but to activist art in situ that have uncontrollable consequences where the happening takes place. And also other things like Antisocial Networking which used Google advertising revenues in order to buy google shares.

Brian Dillon

André Breton and Dogma 95 have in common a confusion between fact and fiction, and put serious and comedy together.

Artists are increasingly encouraged to be academics (“practice led research”). The relationship between Art and Academia is ambiguous. He says that the artist does not like the label of intuition and wants the image of rigour (my unvoiced objection: Certainly not all artists !!!)

The museum values what is not Art in Art: what looks like Art is called kitsch! That’s how the Avant guarde gets into the museum, because it looks different. The Avant guarde blurs the line with everyday life. In order to be successful, the artist produces something that does not look like Art. My unvoiced objection: this is a recent “postmodern” phenomenon. Dada and surrealists certainly did not make it to museum when they first started making strange objects, rather they were insulted n the press by respectable art critics.

What is now valued in Art is the research/knowledge underneath the work. References to other disciplines, “the world as such”. My unvoiced objection: “the world as such” is not the same as “the world as observed by academics”. What did art refer to before ? Didn’t it refer directly to “life” as opposed to an academic representation of life?

Jeremy Millar

Human Forms in Art (2008)

-> taken from the name of a display case in the Pit Rivers Museum (Oxford) that was emptied for building works

-> When interviewing someone for a documentary, people first say what they want to say. You have to keep looking at them without saying anything or stopping the camera and after a while they end up saying what they did not want to say, which often turns out more interesting.

Withdrawal of responsibility by pretending to be just passing on some found material: this is an old tradition in literature.

-> he found something about Duchamp by making a film, a fact that no academic knew of, but someone commented to him that a Phd would be more valued than the movie: the Big Duchamp stained glass “The Bride stripped bare by her bachelors” was apparently inspired by sash windows he saw for the first time in a little town in Kent.

-> My idea: there may be a pun behind this. Sash window = fenêtre à guillotine. A nickname for the guillotine was “La Veuve” (= “The Widow”) which sounds a lot like window. This coincidence may have amused Duchamp -> sacrificing a bride to make a widow?

Jeremy Millar filmed “Ajapeegel” (“Time-Mirror” in Estonian), a video set in the abandoned plant where Andrei Tarkovsky filmed “Stalker”.

Ajapeegel (2008)

Digital Video / PAL 16:9 Anamorphic / Stereo

Narrated by Simon Paisley-Day

The work has been developed from an earlier, abandoned video of the same name, that was to explore the relationship (or lack thereof) between groups of English men on stag-weekends in Tallinn, Estonia, and the three men in Andrei Tarkovsky’s film ‘Stalker’ (1979), which was also shot in and around the city. In ‘Stalker’, the eponymous guide, a scientist and a writer all travel to a room in the ‘Zone’ where, it is said, their inner-most wishes will come true; similarly those men on stag-weekends also make a transitional journey, where, they hope, their desires will be made real also. However, after having filmed a great deal of footage on the original locations in 2005, I found it impossible to realise this planned film, and this new work is, in many ways, a documentary of this failure; an ‘unmaking of’ rather than a ‘making of’ film.

Time-Mirror (2007)

Duration 00:19:20:10

Digital Audio File

This project has been developed from another work, ‘Ajapeegel’, (2008) inspired by Andrei Tarkovsky’s 1979 film, ‘Stalker’, much of which was shot just outside Tallinn, in Estonia. ‘Time-Mirror’ — the English translation of the Estonian ‘Ajapeegel’ — was made by mixing recordings made at the site of a disused hydroelectric power station outside Tallinn, where parts of ‘Stalker’ where shot, with recordings made at Grain Power Station during an artist’s placement there. The similarities between the ‘Zone’ and Grain — the power stations, the desolate landscape, even the military installations — mean that they act as ‘Time-Mirrors’ to one another, or perhaps, more appropriately in this context, as echoes; these are places that reverberate.

Ajapeegel (2005)

Colour Photographs

These are photographs taken in and around Tallinn, Estonia, on locations used for the filming of Andrei Tarkovsky’s 1979 masterpiece, ‘Stalker’; these locations were also used for my own film, Ajapeegel (2008).

The title of these works was taken from that of a book by Tatjana Elmanovits, the first monograph on the Russian director, which was found in a second-hand bookshop in the centre of Tallinn; it means, in Estonian, ‘Time-Mirror’.

Untitled Drawings (2002-onwards)

50 x 70cm

Colour Photograph

Part of a series of photographs that take as their motif the throwing of a metal nut and bandage which is found in Andrei Tarkovsky’s film Stalker (1979). In the film, the Stalker ties bandages to the nuts and uses them to navigate around the mysterious Zone; if the nut travels true through the air and lands safely, then the Stalker and his two companions may travel that way also. While the actions were carried out in similarly uncertain spaces, between nature and industry, and suggest an uncertain presence also, they might also be considered as a rather elaborate means of merely making a line on a piece of paper. The first photograph was made in 2002 in Blean woods, between Whitstable and Canterbury; the remaining photographs were made in Hungary in 2003, during a brief artist’s residency.

One of the speakers?: the inventor of anthropology invented fieldwork techniques because he was forced to stay extensively in Australia in order to avoid being drafted in 1st world war.