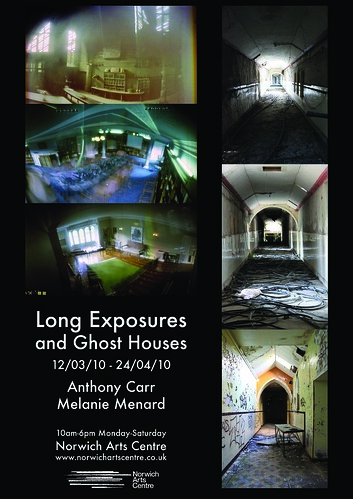

In the 1975 Exhbition New Topographics: Photographs of a Man-altered landscape, photographers started showing an interest in the banal, the creeping uniformed landscapes of suburban America. Previously, landscape photography was aimed at showing the beauty of Nature. The New Topographics had an interest in social comment, irony for some of them. An interesting feature of the show was that all the photographers in it were linked to academia (students or teachers) whereas documentary and landscape photography previously had a long tradition of self taught artists. This show may be seen as the start of a new photographic tradition, still very important in contemporary photography where the subject matter is all and aestheticism either irrelevant or actively avoided. “Conceptual Photography” or “Essay Photography”, one may call this tradition.

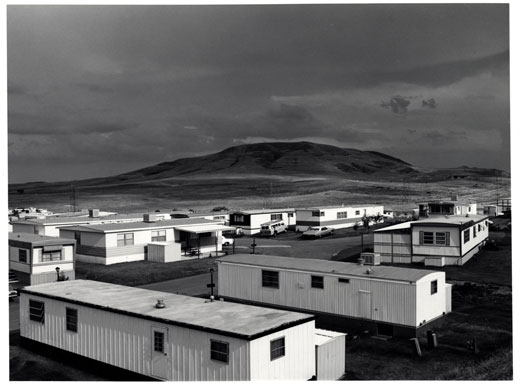

Most of the photographs were black and white and had a rather bland, clinical look, probably due to the flat lighting.

Robert Adams, Tract House, 1974.

Robert Adams, Colorado Springs, 1968.

Henry Wessel, Tucson, Arizona, 1974.

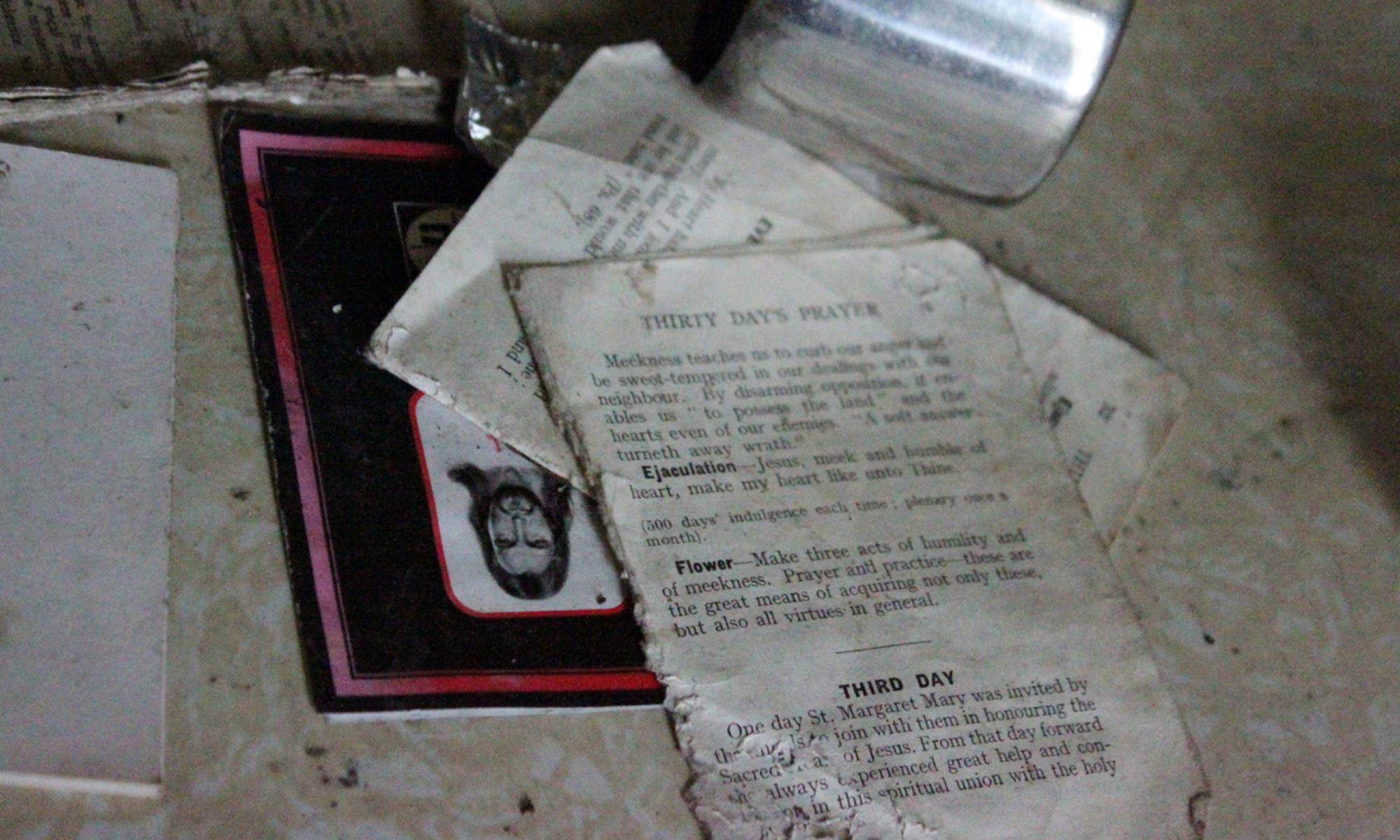

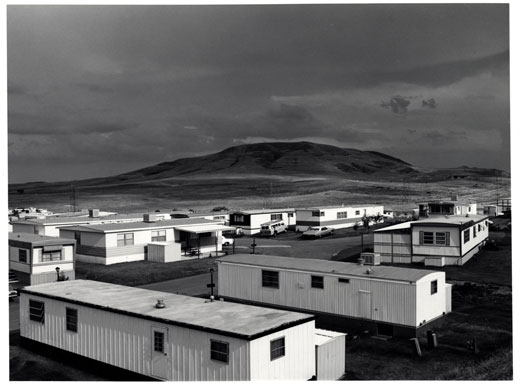

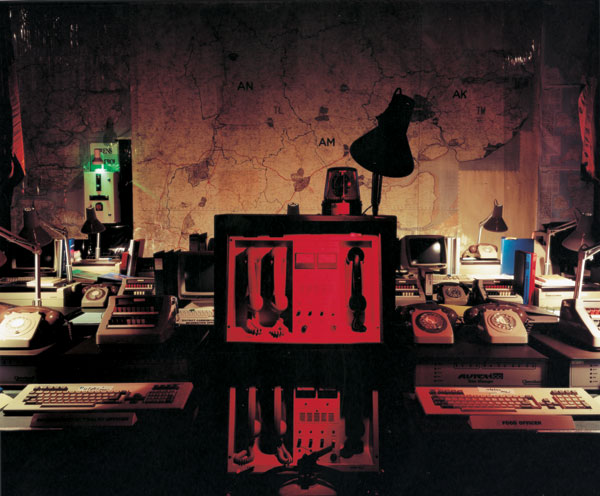

However, other photographs, while still depicting bland, anonymous places, have a more dramatic or eerie lighting that give the pictures at atmosphere of non specified creepiness, of impending doom, of surreality. As though too much bland realism crossed over to the point where the image is not believable anymore, where we get the feeling that we are gazing at a too-perfect movie set.

John Schott, El Nino Motel, 1973.

Robert Adams, Mobile Homes, 1973.

I particularly like the images of Stephen Shore. I like the way the technicolor feel of his pictures evocates Hollywood and the American Dream, while his subject matter reminds how grim it turned for most.

Stephen Shore, 2nd Street East and South Main Street, Kalispell, Montana (August 22, 1974).

Stephen Shore, Alley, Presidio, Texas (February 21, 1975).

His images remind me of the photographs and films of Wim Wenders. I feel in them the same love/hate fascination with the archetypes of the American Dream. “Americans have colonialised our subconscious” says Bruno Winter (Rüdiger Vogler) in “Kings of the Roads”. They look a bit like paintings by Edgar Hopper too.

I think what catches my eye in a documentary photograph is a cinematic look with dramatic lighting and colours that creates an ambiguous contrast with the unstaged nature of the scene.

.jpg)