In October 2011, I was selected to participate in Onedotzero Cascade graduate workshop, where I had the opportunity to attend seminars by Digital Media industry experts and work on a group project responding to a creative brief. As someone trying to move into the Digital Media industry, the main benefit of the workshop was this in-depth training into how to interpret and respond to a brief, the concept of insight and methods of idea generating.

When working as software engineer, I had the opportunity to work on one creative coding project (mathematically generated seascape) where I did both the design and implementation parts and where the design process and workflow was very similar to what takes place in the Digital Media industry. But for most traditional software engineering projects, such a thought process is not required because all user requirements and experience considerations are sorted by Marketing, who then give strict implementation guidelines for the engineer to follow. I was once given the opportunity to take part in the process from the other side and do a marketing research project about ways to prevent hearing loss from personal stereo devices. I had to take into account technical considerations, such as which algorithms were suitable complexity-wise for the chips used by my employer and which algorithms may be adapted to reuse calculations already done by the existing audio system, but also considerations of user experience and psychology: which devices were simple and unobtrusive enough for users to actually bother using them? How to present the hearing protection solution in way that is not patronising or authoritarian, so that the user does not develop an emotional rejection? Research showed that while people tended to react badly to being told to ‘turn the volume down!’, they were more receptive if focus was put on the positive rather than the negative. For example by saying: ‘People usually turn the volume up to compensate for poor intelligibility. Our product gives a better sound quality so you don’t need to turn it as loud to understand everything’ rather than ‘You are damaging your hearing by listening to music too loud’. Presenting the device as providing something extra rather than limiting the user’s behaviour. However these projects were an exception rather than the traditional way of working in software engineering.

As an artist, I was of course very familiar with creative thinking and idea generating but a fine artist defines their own brief. They do not need to understand a third party’s needs, nor to interpret and decode their phrasing of it.

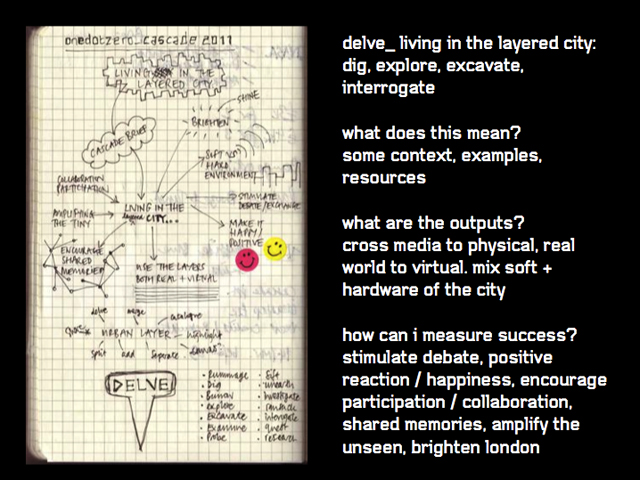

The brief we were given was ‘delve living in the layered city: dig, explore, excavate,

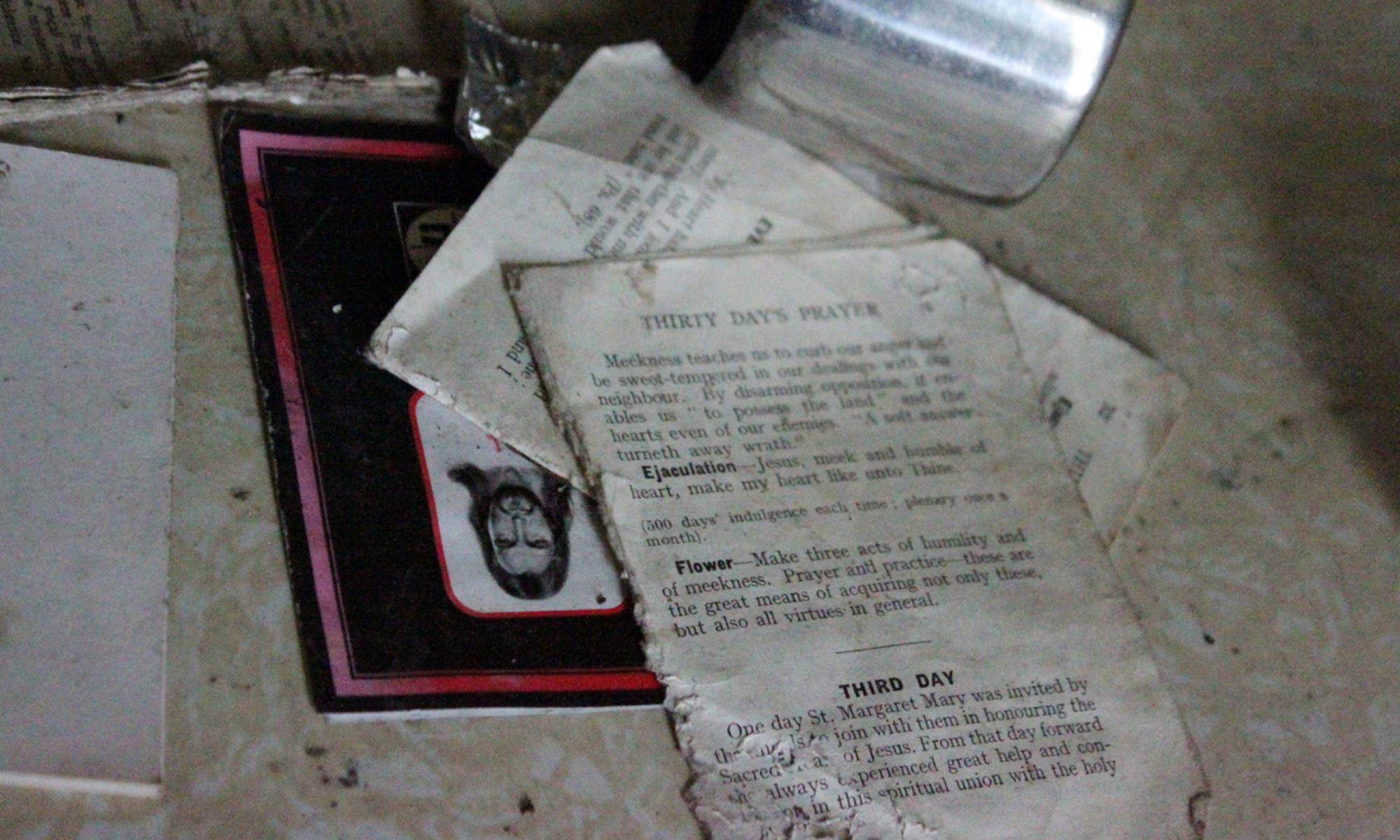

interrogate’ with indications to ‘stimulate debate, positive reaction / happiness, encourage participation / collaboration, shared memories, amplify the unseen, brighten London, interrogate’ and to ‘zoom in, explore below the surface’. The brief suggested various potential angles of interpretation and avenues of exploration, including architecture, advertising and the subversion of it, street art, the collecting of data on the population and its movements. The ones that caught my interest most were ‘look at the everyday as extra ordinary’, and the keywords of ‘layers’ and ‘shared memories’.

An industry expert from advertising agency Mother insisted on the importance of cultural reference points in generating ideas that are relevant and likely to make an impact on an audience. He called this concept ‘insight’, which is coming up with modern, unusual or never thought before take/viewpoint/interpretation on an idea, problem or question.

The word ‘layers’ immediately suggested to me the idea of layers of subjective experience of the city. A city in itself is nothing but a collection of buildings and infrastructures. What makes it vibrant, lively, unique is the experience of the people living in it at any given time, their unique individual vision, their subjective viewpoint and values, the emotional relationship they have with their habitat, be it a sense of home or belonging, a wish to escape, or the desire the change or reinvent the place. I remembered groups of people both online and offline exchanging information about landmarks in London connected to alternative music. I remembered travelling abroad and obsessively looking for landmarks in cities connected to artists or writers whose work I admired. Such information cannot always be found in mainstream tourist guides. Mainstream guides indeed appeal to ‘cultural reference points’, to borrow Mother’s words, but they do so by referring to the lowest common denominator of culture. On top of mainstream culture, the most vibrant and cutting-edge cities, including London, have a myriad of subcultures that cohabit on top or beside each others, like so many layers of semi transparent fabric. Sometimes, two or more of these niche cultures meet, clash and merge to form something new, creating a new shade of colour in the complex fabric of the city.

With this basic idea in mind, I did some research to determine whether my insight had the potential to have some cultural resonance with other people. When researching online, I found the website Exploring 20th Century London, a partnership project between 14 museums in London, including the Museum of London, the London Transport Museum and the Jewish Museum. The project’s aim is to ‘link the objects in the collections with the broader history of London’ and ensure that ‘all objects and images featured on the site speak of the real events and experiences of twentieth-century London’. Two topics covered by the project are ‘Youth Culture and fashion’ and ‘Communities’.

About Youth Culture and fashion, the project explains:

‘During the 20th century London’s position as the place where fashions were set remained the same but the pacemakers changed. Fashions were now led by the young [as opposed to the aristocracy before]. From the bright young things of the 1920s dancing the Charleston to hot jazz; through to the punks of the 1970s pogo-ing to The Damned, the young assumed a new cultural importance in 20th century London.’

The website then proceeds to list various youth cultures through the twentieth-century, relating them to landmark places when relevant, and explain in what measure their influence slowly sipped into the mainstream culture of London.

About Communities, the project says:

‘the sheer size of London’s population has always encouraged the growth of smaller communities within it. Shared experiences bring people together and during the 20th century shared experiences came to include ethnic background and sexuality, as well as religion, neighbourhood and class. London ended the 20th century with a myriad of overlapping communities, each bound together by a sense of people having something in common and a distinct identity.’

So a collaborative project between several London museum believed that the shared experience of overlapping communities of people bound together by a feeling of common identity, either born into (‘communities’) or acquired by cultural choice (‘youth culture’), was a key angle to understand 20th century London. It seemed my insight had cultural resonance after all.

Based on this, I suggested the idea of a ‘subcultural map of London’, an interactive map where the public would be invited to submit landmarks related to various cultures, along with personal memories of events associated with them. People could have shared the story of their first punk concert in an obscure pub, memories of a protest they took part in decades ago, told of a temple where their grandmother took them, or described an art happening they saw in the 60s of which all physical traces have disappeared. I suggested the project could be submitted to the group of museums who might express interest in it.

After group discussion where all my team mates submitted their own insights, the consensus evolved into the idea of unlocking the stories or people living in London or passing through the city. To create a platform where these snapshots of ‘everyday magic’ (to borrow the words of the Surrealists) could be captured and made public to stimulate the viewer’s imagination. People would be invited to upload multimedia content (pictures, video clips, sounds, text) about random things they witnessed on the street, and this content would then be put together to be displayed to viewers on the platform, forming a semi-random narrative. The main challenge posed by this idea was to figure out how to put together disparate multimedia content submitted by various people into a coherent presentation, offering both a compelling narrative and aesthetic appeal. To try and solve this technical challenge, I did some research into Lev Manovich’s database cinema, which constructs dynamic narratives from multimedia elements based on keywords submitted by the audience (these research findings are summarised in another blog post). I thought the concept was promising as it would allow people to get a personalised visual narrative of London tailored to their interests.

The process of coming up with an insight into an issue, collating it with the insights of my colleagues and reaching a consensus on a group project was a very enriching experience.