After being so fascinated by how Robert Polidori photographed ravaged interiors in his ‘After the flood’ series, I looked into other photographers of post Katrina New Orleans in order to find out how they each approached the subject, dealt with the ethical implications, and what aesthetic choices they made.

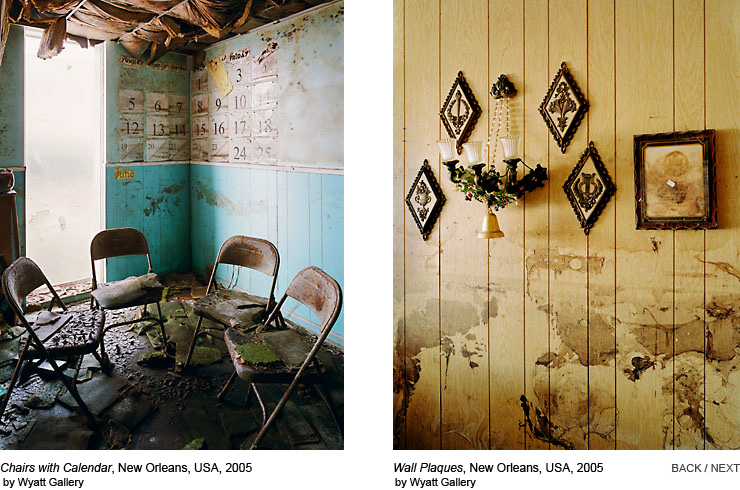

Seesaw magazine presented ‘Remnants’ by Wyatt Gallery and ‘After the Cry’ by Will Steacy.

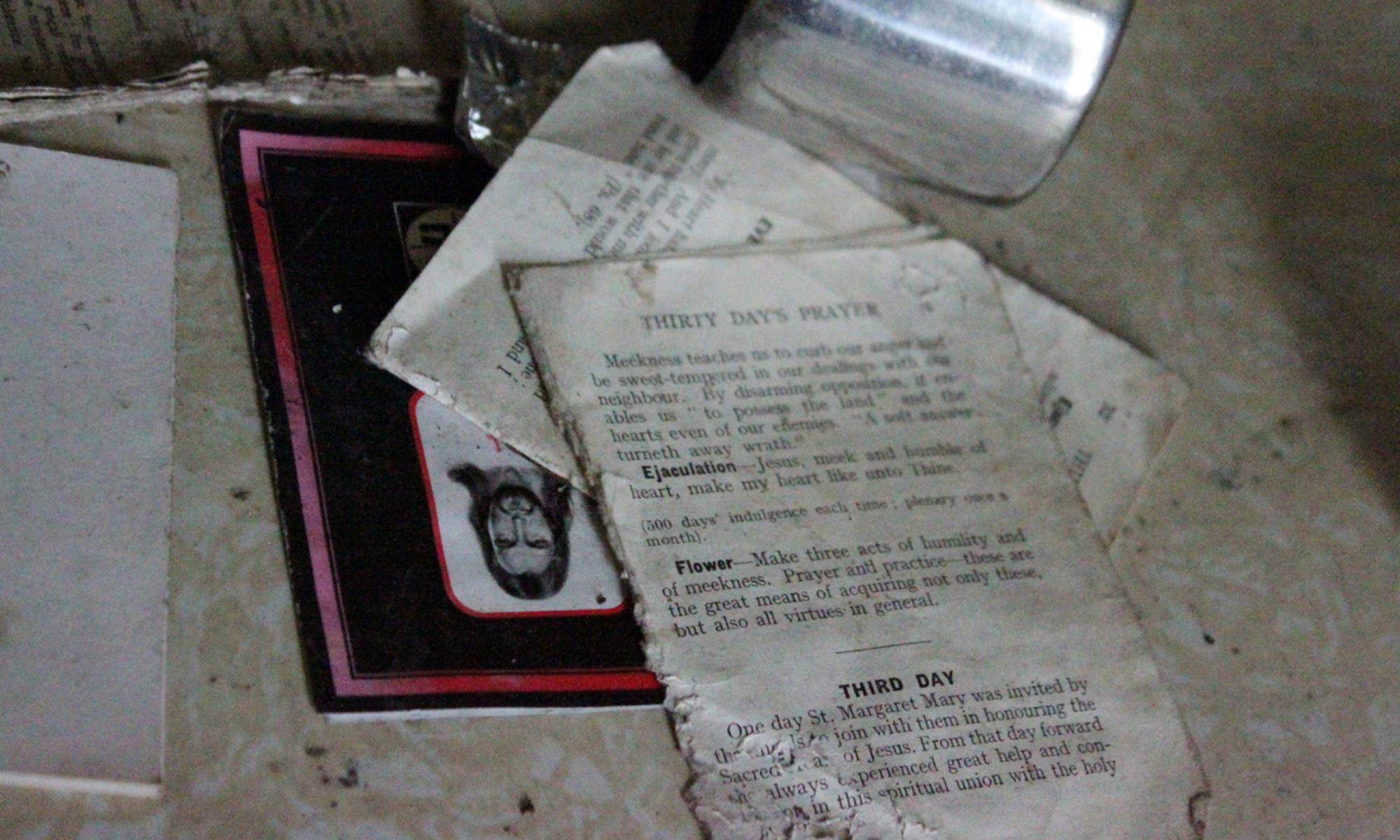

I like the colours, depth and shadows in Wyatt Gallery’s photographs.

Will Steacy adopts a more documentary perspective, focusing on heaps of debris and a near scientific study of molds. He is interested in environmental concerns.

In his photo essay In the Wake of Katrina, Larry Towell adopts the trademark Magnum B&W documentary style. Some pictures devoid of people have a strong haunting quality, particularly long branches and debris near the Mississippi shoreline, a stuffed fox in a glass tank escaped from a museum or collection and a flooded cemetery with the trees and tombs reflected in the water (You need to watch the whole essay on the provided link, I cannot embed particular photos from a flash presentation).

In In Katrina’s Wake: Portraits of Loss from an Unnatural Disaster, Chris Jordan mostly adopt a documentary ‘outdoor’ perspective but a few pictures convey a more aesthecized and disturbing perspective.

I found this ‘Baptist Church, Lower Ninth Ward’ particularly amazing.

Jane Fulton Alt is both a photographer and a social worker. Her photograph series ‘Look and leave’ was taken while she accompanied displaced Lower ninth Ward residents revisit the ruins of their former home as a volunteer worker on the ‘Look and leave’ program. The photographs are accompanied by narrative about the reactions of the people who visited their destroyed homes, but these people do not appear on the photographs. Only empty homes and personal belongings are shown. She comments ‘As a photographer, I prefer to let pictures speak for themselves. But as a social worker, I know that there are some images that stories can illuminate.’ She makes a point that the pictures were not taken while the residents visited their destroyed homes, but on her own after her social worker shift has ended. It is interesting how her perspective as a social worker influence her vision as a photographer, yet the two activities are kept formally distinct. (Again follow the link, the pictures don’t embed.)

John Woodin was raised in New Orleans. A year before Katrina, he photographed his childhood neighborhood and the interior of the homes of his family, focusing on the architecture of the ‘working poor’. After Katrina, he came back and took pictures of the exact same locations. (follow link for portfolios ‘City of memory’ and ‘After the flood’, I cannot embed pictures from a flash presentation.)

In ‘Color of Loss’, Dan Burholder uses HDR (High Dynamic Range) to picture interiors devastated by Katrina in great details despite the darkness. The photographs are supposed to look like paintings. However I find them rather disappointing because I feel the HDR process is taken too far. Moderate HDR enhancement can look striking, but here, the shadows are completely obliterated and most pictures have a completely even lightness on their full surface. To me, the colours appear both saturated and washed out because of this even bright quality to them. The total absence of shadows combined with a choice of lens giving a distorted perspective in some of the pictures cause the feeling of a total loss of the sense of space, at least to me as a viewer. It is possible that the HDR process was taken a bit too far due to over enthusiasm for a back then new technique.

Portrait of Neglect by Debbie Fleming Caffery consist in B&W photographs of displaced residents and ravaged places. There is a striking picture of plaster hands from a statue in front of a wall with peeling pain, but again, I can’t embed from a flash essay.

There are more close up portraits in Debbie Fleming Caffery’s series than in any other work considered. I find it darkly ironic that the work of Robert Polidori has been attacked as immoral for being too anaesthetized, and the documentary work of other people, for example Alec Soth, is sometimes judged dubious for having a too ‘poetic’ perspective. Documentary photography is never neutral, it always shows as much the photographer’s perspective as the events depicted, and it is even clearer when comparing the work of several photographers on a same subject.

As a viewer, Debbie Fleming Caffery’s close up portraits are the only Katrina pictures that made me feel uneasy. Though I’ve never done portraits myself, I’m always fascinated with portraits where the subject is given the opportunity to try and show themselves as they wish to be seen, such as Diane Arbus. Of course, they most of the time will project a different image as intended, or let something slip, but that’s the interest of it, the subject cannot fully control the photograph any more than they can fully control their life, any more than the photographer themselves can fully control the picture they’re taking. But at least the subject is given an opportunity, they’re given power, and the photographer takes some kind of risk than their subject may subvert the picture. I find it exciting that, because there are different inputs to the picture, the result is uncertain. With ‘candid’ portraits showing expressions with a lot of pathos, I don’t think I’m so much made uneasy by looking at people suffering, than by being presented with a picture carrying a label of ‘raw emotion’. It’s almost like the picture carries a label ‘this a truth! this person is not performing for the camera!’. But I only see the finished picture, I cannot see how it was taken, and it is still possible that the subject performs. It’s only my subjective experience as a viewer, but I think what makes me most uneasy with ‘candid’ pictures, is that they give me the impression that the photographer is denying presenting a viewpoint.